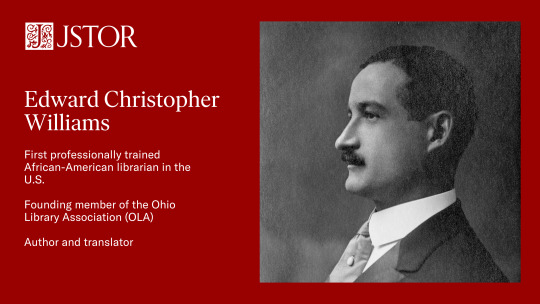

#edward christopher williams

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Edward Christopher Williams (11 Feb. 1871 - 24 Dec. 1929) was a pioneering African American librarian, educator, and scholar who played a vital role in shaping library collections at Western Reserve University (WRU) and Howard University. Born in Cleveland to Daniel P. Williams, a prominent African American figure, and Mary Kilkary Williams, a Clevelander of Irish descent, Williams embarked on a remarkable journey of academic and professional achievement.

Graduating from Adelbert College of WRU in 1892, Williams quickly made his mark as he assumed the role of first assistant librarian at the institution. His dedication and expertise saw him ascend to the position of head librarian in 1894 and university librarian in 1898. Eager to deepen his knowledge, Williams pursued further studies in library science at the New York Library School in Albany, completing the rigorous 2-year program in just one year.

Williams's impact on WRU's library was profound; he significantly expanded its collection and elevated its standards, establishing himself as an authority in library organization and bibliography. His advocacy for the establishment of a school of library science at WRU led to its inception in 1904, where he became an esteemed instructor, offering courses in reference work, bibliography, public documents, and book selection.

A founding member of the Ohio Library Association, Williams played a pivotal role in shaping its constitution and direction. However, in 1909, he left Cleveland to assume the role of principal at M St. High School in Washington, D.C. His tenure there was marked by his unwavering commitment to education and leadership.

In 1916, Williams joined Howard University as university librarian, further cementing his legacy in the realm of academia. Not only did he oversee the university's library, but he also directed Howard's library training class, taught German, and later chaired the Department of Romance Languages.

In pursuit of academic excellence, Williams embarked on a sabbatical in 1929 to pursue a Ph.D. at Columbia University. Tragically, his studies were cut short by his untimely passing later that year.

In 1902, Williams married Ethel P. Chesnutt, the daughter of Charles Chesnutt, a renowned author. Their union bore one son, Charles, who would carry on his father's legacy in the years to come.

Read more about Edward Christopher Williams here.

159 notes

·

View notes

Photo

#nicholas nickleby#nicholas nickleby 2002#charlie hunnam#anne hathaway#jamie bell#romola garai#william ash#timothy spall#stella gonet#andrew havill#alan cumming#tom courtenay#kevin mckidd#nathan lane#david bradley#jim broadbent#juliet stevenson#edward fox#christopher plummer#douglas mcgrath#charles dickens

216 notes

·

View notes

Text

#battlestar galactica#the sound of music#edward james olmos#christopher plummer#william adama#captain von trapp#dilfdecember#commander adama#bsg#sound of music#george von trapp

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

parallels

#I'd have some more if tumblr wasnt dumb#anyways. I'm going fucking crazy#i deadass just bit richard II💀💀#I'm going feral#over these two#and I'm not even done with edward II yet#anyways.#edward ii#richard ii#christopher marlowe#william shakespeare#also tumblr's layout sucks. why cant i space pictures. despair

42 notes

·

View notes

Note

For the kids! 💫

💫 - How Vengeful they are

Gabe,Jer, Susie, and Fritz aren't super vengeful till they remember what William did to them. Then once he got springlocked they were pretty much satisfied.

Charlie is more vengeful but she's more angry on her father's and other kids behalf. She doesn't exactly hate William but she doesn't like him either.

She just wants him to die to let everything to be put to an end so they can all finally rest.

Cassidy is the most vengeful, they remember what William did and they hate him with all their being. They won't let William die ever and Cassidy made UCN (alongside Evan)just to see him suffering to let him experience the pain that he put Cassidy and the other kids through.

They will never let him leave,they will never let him rest, he will suffer for all eternity so that he will never forget the crimes he committed,all the pain and suffering and tears and loss,all the souls in one place just for him ...

#ntr talks#ask game#fnaf au#my au#change of heart au#five nights at freddy's#fnaf gabriel ralston#fnaf gabriel#fnaf susie williams#fnaf susie#fnaf jeremy edwards#fnaf jeremy#fnaf fritz baker#fnaf fritz#fnaf cassidy#fnaf cassidy ralston#fnaf christopher cassidy evan norman afton#fnaf evan#fnaf the one you should not have killed#fnaf vengeful spirit#fnaf mci#fnaf missing children#fnaf missing kids#fnaf ucn#tw death#fnaf#five nights at freddys#fnaf ask game

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Order Of The Garter Service At Windsor Castle

King Charles III, Queen Camilla, Birgitte, Duchess of Gloucester, Prince Richard, Duke of Gloucester, Prince Edward, Duke of Edinburgh, Sophie, Duchess of Edinburgh, Princess Anne, Prince William, Reverend Dr Christopher Cocksworth, The Lady Usher of the Black Rod, Sarah Clarke OBE, Andrew Lloyd Webber, Knight Companion of the Most Noble Order of the Garter, Former Prime Minister Sir Tony Blair, and Catherine Ashton attend the Order Of The Garter Service at Windsor Castle on 17 June 2024 in Windsor, England.

The Order of the Garter is the oldest and most senior Order of Chivalry in Britain.

Knights of the Garter are chosen personally by the Sovereign to honour those who have held public office, contributed in a particular way to national life, or who have served the Sovereign personally.

📸: Samir Hussein/ WireImage / Kirsty Wigglesworth - WPA Pool / Getty Images / Chris Jackson - WPA Pool /Getty Images

#Order Of The Garter Service#Order Of The Garter Service 2024#King Charles III#Queen Camilla#Prince William#Prince Edward#Princess Anne#Sophie Duchess of Edinburgh#Duke of Edinburgh#Duchess of Edinburgh#Prince Richard#Duke of Gloucester#Duchess of Gloucester#Birgitte Duchess of Gloucester#Tony Blair#Andrew Lloyd Webber#Catherine Ashton#Sarah Clarke OBE#Reverend Dr Christopher Cocksworth#Windsor Castle#St George's Chapel#Alastair Bruce

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

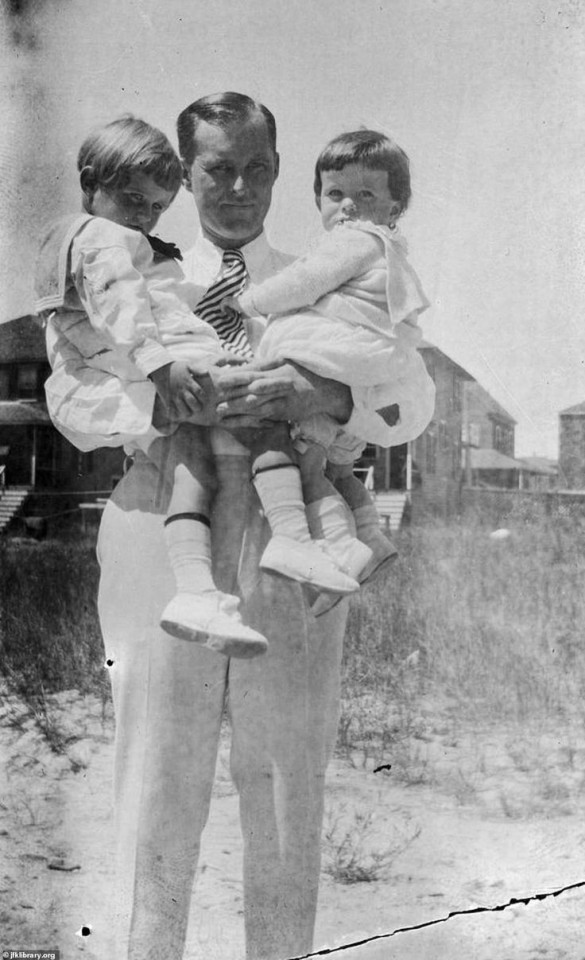

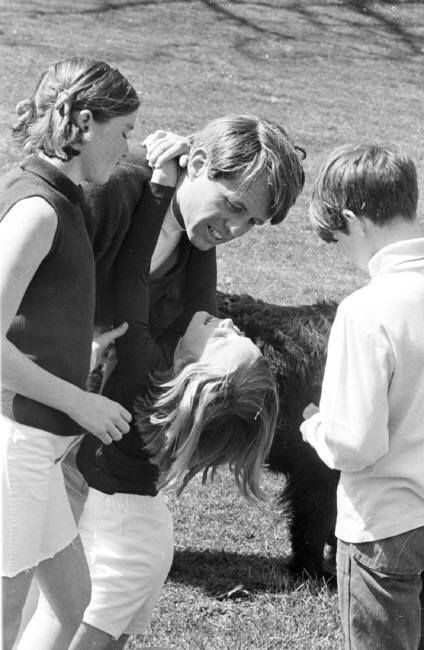

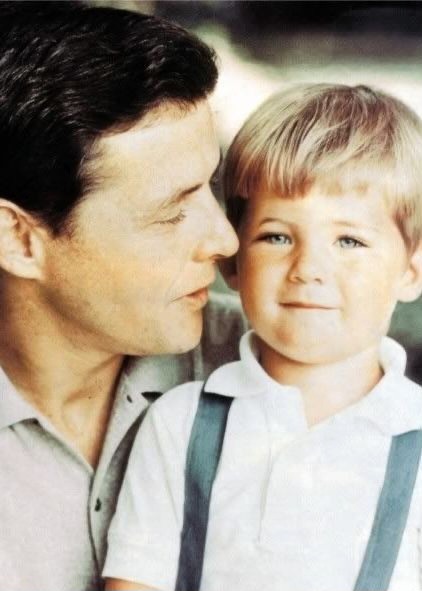

Happy Father's Day❤️🎉✨️

#Joseph P. Kennedy Sr#Joseph P. Kennedy Jr#John F. Kennedy#Caroline Kennedy#John F. Kennedy Jr#Sargent Shriver#Bobby Shriver#Peter Lawford#Christopher Lawford#Sydney Lawford#Victoria Lawford#Robert F. Kennedy#Courtney Kennedy#Michael Kennedy#Kerry Kennedy#Stephen Smith#William Kennedy Smith#Edward M. Kennedy#Kara Kennedy#Happy Father's Day

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Haterating and hollerating in the 1980s. None of these movies has any meaningful wlw content, so just assume the answer to "CONTAINS LESBIANS?" is "No."

VIDEODROME (1983): I'd never actually seen all of this loopy, surreal David Cronenberg thriller about an opportunistic Canadian TV station president (James Woods) who becomes convinced that a mysterious series of pirate broadcasts showing scenes of torture and murder might be the Next Big Thing, resisting all attempts to warn him off until it's far too late. Like SCANNERS (which I had seen), its influence has been so outsized that much of it feels familiar even on first viewing, including the film's now-notorious forays into body horror, which, if you're expecting them, are no longer really that shocking (although they are often memorably icky). What's less expected, and thus more striking, is the film's Pynchon-like (Pynchonian? Pynchonesque?) deadpan absurdity; the story is full of characters with names like Blanca O'Blivion (Sonja Smits), daughter of Marshall-McLuhan-like media theorist Brian O'Blivion, and Barry Convex (Leslie Carlson), a sinister optician who's also a defense contractor. It's really very funny, in the same mode as John Carpenter's later THEY LIVE. Judging by the sheer density of ridiculous stuff happening even around the edges, like the brief snippet we see of the weird call-in show hosted by Nicki Brand (Debbie Harry, who's less prominently featured than I'd been given to expect), I can only assume it was intentional, although Cronenberg's narrative straight face and the outsize reactions to the goopy "videocassette orifice" stuff stood in the way of its being recognized as a comedy. (That it's a satire should of course be obvious.) VERDICT: One of those movies you need to see for reasons of cultural literacy, even if it's not really your thing, but perhaps not while eating.

GOTCHA! (1985): Before finding his niche on the TV show ER, Anthony Edwards had a burgeoning career as one of the more obnoxious of the many obnoxious young male stars of the '80s, offering an insufferable combination of earnestness and smarm in films like REVENGE OF THE NERDS and this dumb teen adventure, obviously intended to capitalize on a then-popular campus fad. Horny 18-year-old UCLA veterinary student Jonathan Moore, whose favorite hobby is the titular paintball assassination game, decides to go to Europe with a friend (Alex Rocco, who has more charisma in his minor supporting role than Edwards musters in his entire '80s filmography) and falls for a hot older woman called Sasha (Linda Fiorentino), who soon involves Jonathan in some deadly real-world espionage. The midsection, set in Paris and Berlin, is an okay if unremarkable Cold War thriller, with Edwards relatively tolerable as a fish out of water; the movie's best scene has him hitching a ride with a van full of German punks who love DALLAS. Unfortunately, the third act returns to L.A. and attempts to pay off the paintball-game setup, with preposterous results. Also, if you're much older than the protagonist, the way the story wraps up Jonathan's relationship with Sasha will likely seem a little creepy. VERDICT: Misses the mark.

INTO THE NIGHT (1985): Oddball black comedy thriller starring Jeff Goldblum as Ed Okin, a depressed, insomniac aerospace engineer who over the course of one long night becomes the unlikely savior of a beautiful woman (Michelle Pfeiffer) who's being pursued by an assortment of deadly enemies. Goldblum has fun with his character, who hasn't slept in days and is no longer capable of any emotional response beyond mild dismay (something that becomes progressively funnier as the situation escalates), and he has excellent rapport with Pfeiffer, who's not so much a femme fatale as an aging good-time girl who's worn out her welcome just about everywhere. Unfortunately, they're saddled with a script that often seems like an unfinished draft, with a murky, rather racist plot that's full of setups for gags whose punchlines are still marked "TBA," and punctuated by bursts of violence that are frequently meaner than called for (the fate of the Kathryn Harrold character is especially nasty, and completely gratuitous). Dan Ackroyd, David Bowie, Vera Miles, Irene Papas, and other prominent stars pop up in minor roles, usually for no more than a scene or two, and director John Landis peppers the film with guest appearances by other film directors (including Roger Vadim, Paul Mazursky, David Cronenberg, and Jim Henson, among others), which is distracting if you recognize them and puzzling if you don't. VERDICT: Goldblum and Pfeiffer are great, but Landis's weird indulgences leave it feeling like a private joke.

MANHUNTER (1986): Mesmerizing Michael Mann adaptation of the Thomas Harris novel RED DRAGON, with William Petersen as Will Graham, Dennis Farina as Jack Crawford, Tom Noonan as the "Tooth Fairy" killer, Joan Allen as Reba, and Brian Cox as Hannibal Lecter (for some reason spelled "Lecktor"). It has a very different narrative center of gravity than later Hannibal Lecter movies or the HANNIBAL TV show, though it's no less stylized, with striking use of color and music (most memorably in the finale, which uses Iron Butterfly's "In-A-Gadda-Da-Vida" diegetically). Like most such stories, it's ideologically objectionable — though arguably less so than THE SILENCE OF THE LAMBS — but it's certainly effective, and less hokey than the 2002 adaptation with Ed Norton. Long, slow-paced (particularly in the director's cut), and not very deep, but if you catch it in the right frame of mind, its blend of chilly psychological detachment and procedural minutiae is almost hypnotic. VERDICT: A movie to dissociate to.

THE MANHATTAN PROJECT (1986): If OPPENHEIMER struck you as too pompous and amoral, try this decent if implausible mid-'80s teen movie about a high school science prodigy (Christopher Collet) who decides to protest the secret DOE lab run by his mom's nerdy new scientist boyfriend (John Lithgow) by stealing some plutonium from the lab with the help of his aspiring teen reporter sort-of girlfriend (a babyfaced Cynthia Nixon) and then building his own atomic bomb. The first half relies too heavily on its hyper-competent (and singularly arrogant) kid hero effortlessly outwitting doofus adults, although it works well enough on its own terms. Things pick up in the exciting third act, which is enlivened by a terrific performance by Lithgow, supported by John Mahoney as a hard-bitten Army colonel who's decided the best way to contain the situation is to kill the boy as soon as they can separate him from the bomb. Collet is quite good, if not terribly likeable; Nixon does her best with an underwritten supporting role. VERDICT: The intended moral point ends up a little muddy, but an attempt was made, which is more than one can say for Nolan's overblown epic.

MIRACLE MILE (1988): AFTER HOURS at the end of the world: What begins as a treacly romance about a dweebish musician (Anthony Edwards at his most objectionably saccharine) falling for a diner waitress (Mare Winningham with a truly unfortunate haircut) takes an extremely dark turn as our hapless hero answers a misdialed pay phone call and learns that nuclear war is about to begin, setting him on a frantic, surreal late-night quest to find his dream girl and get them both out of L.A. before it's destroyed by (presumably) Soviet missiles. It's a frightening premise for a perfectly dreadful script whose painfully contrived setup, cartoonish characters (including Denise Crosby as an unlikely diner patron who seems to know something about what may be going on), and uneasy half-comic tone undermine its credibility at every turn. The urgency and uncertainty of the threat are enough to hold your attention for about an hour, but from there, the story has nothing left to do but to play out the string, leading to an incredibly nihilistic finale not recommended for anyone in an emotionally fragile state. VERDICT: Memorably weird, but not in a good way.

#movies#hateration holleration#videodrome#david cronenberg#gotcha!#anthony edwards#linda fiorentino#into the night#john landis#jeff goldblum#michelle pfeiffer#manhunter 1986#michael mann#william petersen#miracle mile#denise crosby#marshall mcluhan#thomas pynchon#the manhattan project 1986#christopher collet#john lithgow#cynthia nixon#john mahoney

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

'AFTER THE UNITED STATES COMPLETED its first successful test of an atomic weapon on July 16, 1945, enabling, less than a month later, the expeditious slaughter of an estimated one hundred forty thousand Japanese people in Hiroshima and seventy thousand in Nagasaki, most of them civilians, recollections of those present at the test site on a remote desert plain in New Mexico suggest that Robert Oppenheimer, the charismatic director of the secret laboratory responsible for designing the bomb, may have been at a loss for words. “It worked,” is all Oppenheimer’s brother Frank remembers the theoretical physicist mustered in the moments after the culmination of a four-years-long, $2.2 billion campaign involving the labor of some one hundred thirty thousand people to construct a weapon capable of killing just as many.

Later, in a 1948 cover story for Time magazine, Oppenheimer had the chance to insert something a bit more literary into the historical record, telling his interviewer that a line from the Bhagavad Gita flashed through his consciousness at the moment of the blast: “Now I am become death, the shatterer of worlds,” which he amended in a 1965 NBC television documentary, relying on his own translation of the Sanskrit text, to “destroyer of worlds,” which has a more apocalyptic ring to it.

In Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer, our hero-physicist, played by Cillian Murphy, first utters the line while he’s balls-deep in a troubled communist named Jean Tatlock (Florence Pugh). It’s one of several instances of speculation, if not outright historical infidelity, in Nolan’s transfiguration of American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer by Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin into an operatic tragedy-cum-thriller for the big screen. This is a summer blockbuster, after all, and if we’re going to have three hours of chalkboard equations and security clearance hearings, we’re going to need to see the father of the atomic bomb fuck.

To tell the story of “the most important person who ever lived,” Nolan, who must have fancied himself uniquely qualified for the job, concocts an elaborate structure, switching between a “subjective” color and an “objective” black and white as he pinballs across three decades of the twentieth century, introducing us along the way to a cast of physicists, communists, communist physicists, presidents, professors, bureaucrats, spies, lovers, generals, colonels, congressmen, and war planners, all of it framed by the 1954 security clearance hearing that resulted in Oppenheimer’s expulsion from the establishment on spurious charges, and the 1959 congressional confirmation hearing of the film’s villain, Lewis Strauss, played by a Robert Downey Jr. (clearly thrilled to have been cut loose from the Marvel Cinematic Universe), who orchestrated the campaign against Oppenheimer five years earlier, in part because Oppenheimer embarrassed him one time before Congress but also because Strauss had a propensity to conclude that anyone who repeatedly disagreed with him, as Oppenheimer did, was a traitor. It’s a lot.

Somehow it works, sustaining tension through what is, increasingly, a rarity: a movie that’s mostly people talking in rooms. But as the laws of physics and Hollywood require, the complexity of plot is met with an equal and opposite force: thematic simplicity. This is a tragedy, we are repeatedly told, that turns on a Great Man’s blindness, to the exclusion of much else. “How could a man who saw so much be so blind?” Strauss asks early on to drive home the point.

Our blue-eyed sad boy emerges into the atomic age, repentant, bent on preventing the annihilation of the human race.

To get at the answer, there’s a lot of ground to cover. And so, at a frenetic clip, we follow Oppenheimer through his school days at Cambridge (where he leaves a poisoned apple on the desk of his tutor, a worn-out bit of symbolism Nolan, thankfully, does little with) and later at the University of Göttingen (where a montage of Oppenheimer staring intently at a Picasso painting, reading T.S. Eliot’s “The Waste Land,” and dropping the needle on Stravinsky helpfully telegraphs to the unconvinced that we’re dealing with a sensitive genius) before he’s appointed, at the age of twenty-five, to an assistant professor of physics post at Berkeley, a campus awash in gin and radicals. There, he meets and falls in love with Tatlock, who tries to dye his wool red but settles for pink while alternating between accepting and spurning his advances. Soon he meets Katherine “Kitty” Puening, a thrice-married booze hound and former communist played with wild-eyed mettle by Emily Blunt, with whom he has a child and marries but not before Lise Meitner and Otto Frisch split the atom offstage in Berlin, proving the feasibility of the atomic bomb, which becomes a real cause for concern when Hitler invades Poland the following year. Oppenheimer gets pulled into the top-secret Manhattan Project by General Leslie Groves (Matt Damon, less of a distended thumb than the real man but still well-played), who installs him as the director of what would become the Los Alamos laboratory over the protestations of numerous pinko-fearing officials.

By the late spring of 1945, Oppenheimer and a small town’s worth of physicists are nearing completion of their little “gadget,” which the United States, having missed the chance to nuke the Nazis, plans to use against Japan—but also to, as the real Groves put it as early as 1944, “subdue the Russians.” The Japanese government was grasping about for acceptable terms of surrender, which select portions of the U.S. military apparatus knew but ignored and later downplayed in favor of framing the matter as a choice between launching a protracted land invasion that would have cost hundreds of thousands of American lives and dropping two weapons of mass destruction. Nolan doesn’t wade too far into the nitty-gritty here, though we do get to watch the meeting in which Secretary of War Henry Stimson graciously strikes Kyoto off the list of possible targets because he had a great time there on his honeymoon.

To the consternation of those who perceive representation to be the chief measure of a film’s merit, Nolan pointedly declines to depict the actual bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki; instead, we watch as Oppenheimer becomes so overwhelmed with guilt while giving a speech to a violently enthusiastic crowd at Los Alamos that he hallucinates stepping on the incinerated corpse of a Japanese civilian. (Nolan apparently penned the screenplay in the first-person, presumably because he feels a degree of affinity with his protagonist.)

And thus our blue-eyed sad boy emerges into the atomic age, repentant, bent on preventing the annihilation of the human race. The real Oppenheimer never publicly apologized for his role in the bombings, but in the immediate aftermath of the war, he did try—and fail—to make headway on the international regulation of atomic weapons while wringing his hands about how physicists had “known sin” and issuing warnings to the public about the dangers of a nuclear arms race. For the sake of time, Nolan emphasizes Oppenheimer’s role, as the chairman of the General Advisory Committee to the Atomic Energy Commission, in formally advising the government against pursuing a crash program to develop a “super,” or hydrogen, bomb in 1949. At the time, the H-bomb was thought to be technically unfeasible, but even if it could be developed it might by dint of its awesome destructive power become “a weapon of genocide.” It seemed to make more sense to put American resources toward building conventional nuclear weapons, perhaps “tactical” nuclear weapons for use on the battlefield, as the real Oppenheimer advocated less than a year into the Korean War. This was a strategic pivot from his 1946 stance that nuclear bombs of any size were “a supreme expression of the concept of total war,” though perhaps not as extreme as his consideration of “preventive war” against the Soviet Union in 1952, an idea he had scorned a mere three years earlier. The evolution, which is to say general tack to the right, of Oppenheimer’s thinking didn’t much matter to those in power, who could not forgive him for declining to offer a full-throated endorsement of developing bombs hundreds of times more powerful than the ones dropped on Japan. In their view, this was evidence of communist sympathy, perhaps treason.

Oppenheimer’s contradictions and occasionally elastic thinking are downplayed; Nolan needs to keep his protagonist’s postwar moral compass obdurately fixed for dramatic import as we near the final showdown: the 1954 security clearance hearing, covertly orchestrated by Strauss, then chairman of the AEC, in the wake of a list of charges against Oppenheimer claiming that, in addition to obstructing the development of the hydrogen bomb, the erstwhile fellow traveler was “more probably than not . . . an agent of the Soviet Union,” as William L. Borden, the staff director for the Joint Committee on Atomic Energy, put it after poring over Oppenheimer’s FBI file, by then over seven thousand pages long. Oppenheimer’s numerous enemies wished to, as Edward Teller put it, see him “defrock[ed] in his own church,” and this was their chance. The hearing, convened in an anonymous D.C. conference room in April and calling numerous prominent physicists and officials as witnesses, would thus determine if a man prone to dissent ought to have his top-secret “Q” clearance renewed, even though Oppenheimer was, by that time, only acting as an occasional consultant to the GAC he once chaired. At the height of McCarthyism, dissent had become confused with disloyalty, and Oppenheimer would, after spending some twenty-seven hours in the witness chair, become its most prominent victim.

For a film to play in thirty-six thousand theaters opening weekend in this country, it needs more than Florence Pugh’s tits.

Oppenheimer was assured the transcript of the proceeding would never be made public, but Strauss (who got his comeuppance five years later when Congress declined to confirm his appointment to Eisenhower’s cabinet) saw to it that the government printing office published it promptly, all three thousand typewritten pages of it. The media was quick to recognize that the father of the atomic bomb had been martyred in an “Aristotelian drama,” “Shakespearean in richness and variety,” with “Eric Ambler allusions to espionage,” a “plot more intricate than Gone With the Wind” with “half again as many characters as War and Peace,” much of which could also be said of Nolan’s film, which finds screen time for former Nickelodeon stars and also Rami Malek, who cannot act.

Nolan, too, recognizes the Shakespearean qualities of the hearing and quotes liberally from the best parts, already helpfully curated in American Prometheus. Though, again, we are not shown the points where Oppenheimer declines to adopt, unequivocally, the “moral” position Nolan wishes to ascribe to him—in fact, he preferred to “leave the word ‘moral’ out of” the discussion of the hydrogen bomb, though he nevertheless “had qualms about [it].” The hydrogen bomb was a “dreadful weapon,” but it was also “from a technical point of view . . . a sweet and lovely and beautiful job.” As for the dropping of the atom bomb on Hiroshima, he “set forth arguments against dropping it,” but “did not endorse them.” Which is not to say that Oppenheimer was a moral relativist, adopting and abandoning positions exclusively for the sake of personal advantage. He wasn’t and he didn’t, though he was certainly more complex, more frustratingly human, than his IMAX representation.

Don’t get me wrong; Oppenheimer is a superb achievement and will be appropriately showered with astronomical box office returns, critical praise, and awards (Oscars most likely for both Murphy and Downey Jr.), but despite Nolan’s nerdishly painstaking attention to detail (we learn, for instance, Oppenheimer sometimes dipped his martini glasses in lime juice and honey), he shows little interest in offering up anything that might complicate the audience’s notion of Oppenheimer as a Great Man of History guided by idealism, blinded by naivete, and doomed by his temerity to stand astride the arms race, yelling stop.

I’ve long thought the tragedy of Oppenheimer’s life would best be suited to the stage, and I’m not the first: in 1964, three years before Oppenheimer died of throat cancer, the German playwright and psychiatrist Heinar Kipphardt, blustering about Hegel’s advice to lay bare the “core and significance” of historical events by freeing them from “adventitious contingencies and irrelevant accessories,” adapted the 1954 hearing into a tediously didactic two-act play. At the start of each scene, various themes and guiding questions are projected onto a scrim: “IS THERE SUCH A THING AS HUNDRED-PER-CENT SECURITY?” “LOYALTY TO A GOVERNMENT. LOYALTY TO MANKIND.” At the end, characters approach the footlights to browbeat the audience with a pedantic soliloquy, including Roger Robb, the hearing’s prosecutor, who wonders, “Do we dissect the smile of a sphinx with butchers’ knives? When the security of the free world depends on it, we must.”

The worst comes from the Oppenheimer character himself, who, after being served the verdict that spelled the end of his formal access to the beltway barbarians, steps forward to bemoan that, “We have been doing the work of the Devil, and now we must return to our real tasks.” The real Oppenheimer—who later clarified that when he claimed physicists had “known sin,” he actually meant the sin of pride—never went this far. So it’s no surprise he hated the concluding monologue and the play’s general allergy to ambiguity so much that he threatened legal action against its author, though he eventually agreed to sit through a production in France, which he liked a bit because it relied more heavily on the official transcripts, though he still felt Kipphardt had “turned the whole damn farce into a tragedy.”

There can be few direct comparisons between a spartan stage play penned by a psychiatrist incapable of originality and a $100 million thriller written by an accomplished egomaniac, but they do share something in how they approach their protagonist, sanding off his ambiguities and contradictions so as to present a tragic figure haunted by what he’s wrought. Perhaps Nolan can’t be entirely blamed: for a film to play in thirty-six thousand theaters opening weekend in this country, it needs more than Florence Pugh’s tits; it must be obvious, possessed of a storybook sense of morality, expurgated of any evidence that J. Robert Oppenheimer was, though certainly distressed by the implications of nuclear weapons, not above pragmatic concessions he thought might help him retain the beltway power and influence he won after snatching fire from the gods and handing it to man.

His was a strategic error not uncommon to well-intentioned Washington insiders: the naive belief that, through a careful balancing act of dissent, strategic ambivalence, and acquiescence, one can use power to enact more positive change from within than without—a form of blindness, surely. Oppenheimer was a man who appeared to want it both ways: to play the part of the somber public intellectual as well as the consummate insider. That was his undoing, the true crux of the man’s tragedy. There is not much room for such everyday failings here, even in 70mm.'

#Oppenheimer#Christopher Nolan#Cillian Murphy#Jean Tatlock#Florence Pugh#American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer#Kai Bird#Martin J. Sherwin#Lewis Strauss#Robert Downey Jr.#Marvel Cinematic Universe#T.S. Eliot#The Waste Land#Katherine “Kitty” Puening#Emily Blunt#Leslie Groves#Matt Damon#Los Alamos#William L. Borden#Edward Teller

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

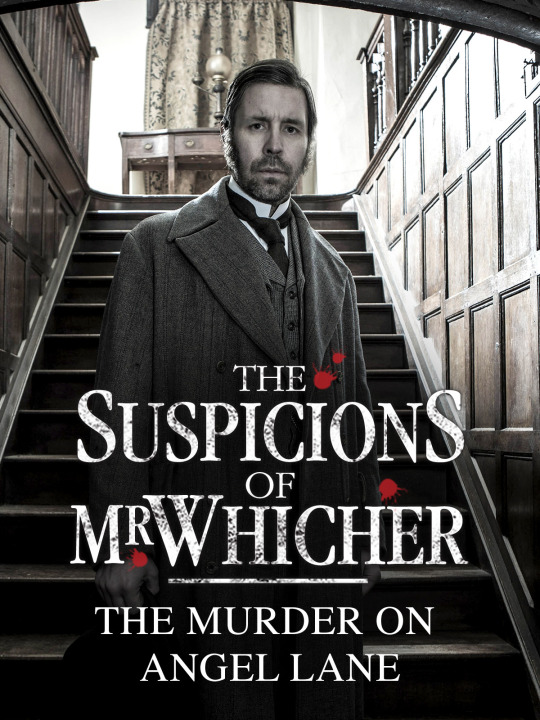

"THE SUSPICIONS OF MR. WHICHER: THE MURDER ON ANGEL LANE" (2013) Review

"THE SUSPICIONS OF MR. WHICHER: THE MURDER ON ANGEL LANE" (2013) Review

Over a decade ago, the ITV network aired a television adaptation of Kate Summerscale's 2008 true life crime book, "The Suspicions of Mr. Whicher or The Murder at Road Hill House", starring Paddy Considine. The movie proved to be such a success that producer Mark Redhead had followed up with three other television productions featuring the main character, Jack Whicher. The first of these sequels was 2013's "THE SUSPICIONS OF MR. WHICHER: THE MURDER ON ANGEL LANE".

The 2013 television movie began with Jack Whicher coming to the aid of a wealthy middle-age woman, when a young thief snatches her purse inside a London pub in London. After retrieving her purse, Whicher discovers that the woman, Susan Spencer, is searching for her missing niece, a 16 year-old girl named Mary Drew. Miss Spencer learns of Whicher's old position as a police detective and hires him to find the missing girl. Whicher eventually discovers Mary's brutally murdered body inside the police morgue. Both eventually learn that before her death, Mary had given birth to a child and someone had stolen a family heirloom from her. Miss Spencer hires Whicher to act as her private consultant and find Mary's killer.

When I first saw "THE MURDER ON ANGEL LANE", I had assumed the story began sometime after the events of 2011's "THE SUSPICIONS OF MR. WHICHER: THE MURDER AT ROAD HOUSE HILL". It took a rewatch of this second television movie for me to realize that it was set during the events of the 2011 movie - sometime between the four or five years between Mr. Whicher's failure to get the killer prosecuted for murder and the latter's eventual confession. I was able to ascertain this conclusion, due to the hostile behavior of Police Commissioner Richard Mayne toward Whicher and the one of the supporting character's comments. This setting also explained Whicher's occasional doubts regarding his skills as a detective. Now whether the other two Whicher television movies that followed were also set during this period is a matter I will eventually discover.

Unlike "THE MURDER AT ROAD HOUSE HILL", "THE MURDER ON ANGEL LANE" proved to be a genuine "whodunnit" story. This particular case was not some true crime narrative. And Whicher did not discover the antagonist's identity until the finale act. I am not saying that this particular difference made the 2013 television movie an improvement over the first one. But in a way, it felt a little refreshing to view a murder mystery/period drama, instead of a mere true life case set in the far past. "THE MURDER ON ANGEL LANE" started as an investigation into the disappearance of a well-born adolescent managed to transform into a lot more. Like "THE MURDER AT ROAD HOUSE HILL", this story also proved to be a family drama beset with murder, betrayal and corruption. But unlike the 2011 movie, greed also play a major role in "THE MURDER ON ANGEL LANE". I thought screenwriter Neil McKay and director Christopher Menaul handled the movie's narrative very well, with a minor exception or two. I also admired how McKay used the unresolved events of THE MURDER AT ROAD HOUSE HILL" to not only provide the Whicher character as an emotional obstacle for him to overcome, but also an excuse to place him in the dangerous situation that he found himself in the movie's final act.

I do have a few complaints about the plot for "THE MURDER IN ANGEL LANE". And it centers around a small group of quibbles regarding the television movie's final act. Whicher's investigation led him to a third visit at an insane asylum, where he found himself incarcerated as a patient. A part of me felt relieved that this particular scenario lasted less than five minutes. However, another part of me found this sequence rushed and contrived for it did not take Whicher long to receive help in making his escape. Following on the heels of the asylum sequence, Whicher finally confronted the murderer. But he did so alone . . . and without contacting his old friend, Chief Inspector Adolphus "Dolly" Williamson or other members of the Metropolitan Police. I understand why Neil McKay had written the confrontation scene this way. I simply found it implausible and wish he could have created another way to close the case.

I certainly had no complaints about the movie's production values. David Roger returned to the "MR. WHICHER" series to serve as production designer. As he did for "THE MURDER AT ROAD HOUSE HILL", Roger managed to re-create the look and style of early 1860s Britain with the additional work of Paul Ghirardani's art direction and the set decorations of Jo Kornstein, who had also worked on the "ROAD HOUSE HILL" production. Only in this production, his vision extended to the streets of London. Tim Palmer served as the film's cinematographer. I thought he did a solid job, but his work did not exactly blow my mind. Lucinda Wright also returned to serve as the movie's costume designer. As she did for the 2011 television movie, her work for "THE MURDER ON ANGEL LANE" perfectly recaptured the early-to-mid 1860s without being either shoddy or over-the-top.

Paddy Considine returned to reprise his role as Jack Whicher. As he had done in the first movie, the actor did an excellent job of quietly capturing the character's reserve nature, intelligence and skill for criminal investigation. However, Considine managed to add an extra touch of poignancy, as he project Whicher's occasional bouts of insecurity in the wake over the Road House Hill case and his minor failures during his investigation of this case. Both William Beck and Tim Piggott-Smith reprised their roles as "Dolly" Williamson and Commissioner Mayne from from the first film. Like Considine, both actors gave first-rate performances. And both added extra touches to their performances - especially in their characters' attitudes toward Whicher - in the wake of the Road House Hill debacle. Olivia Colman provided the movie's emotional center as the well-born Susan Spencer, who hired Whicher to first, find her niece Mary Drew and later, find the latter's killer. She and Considine, who had co-starred in the 2007 comedy, "HOT FUZZ", worked very well together. Shaun Dingwall gave a very subtle performance as Inspector George Lock, the main investigator of Mary's murder and the only one willing to give him a chance in helping the police. The television movie also featured solid performances from Mark Bazeley, Alistair Petrie, Billy Postlewaite, Angela Terence, Justine Mitchell, Sean Baker, Sam Barnard, Christopher Harper and Paul Longely.

Of the four "MR. WHICHER" television movies, I must admit that "THE SUSPICIONS OF MR. WHICHER: THE MURDER ON ANGEL LANE" is my least favorite. I believe the last fifteen to twenty minutes had been marred by some contrived writing that I believe had rushed the narrative's pacing. However, I still believe it was a first-rate production in which screenwriter Neil McKay had created an intriguing whodunnit involving a major family feud, betrayal and greed. And director Christopher Menaul, along with a talented cast led by Paddy Considine had skillfully conveyed McKay's story to the screen.

#kate summerscale#neil mckay#christopher menaul#jack whicher#the suspicions of mr. whicher#the suspicions of mr. whicher: the murder on angel lane#paddy considine#olivia colman#william beck#shaun dingwall#alistair petrie#victorian age#tim piggott-smith#justin edwards#billy postlethwaite#siobahn o'neill#mark bazeley#angela terence#justine mitchell#sean baker#sam bernard#christine harper#paul longely#road house hill#costume drama#period drama#period dramas

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

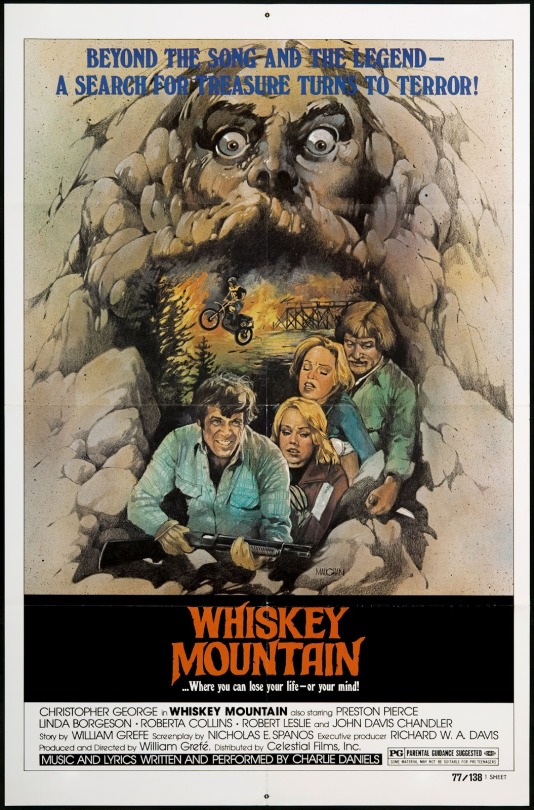

Whiskey Mountain (1977)

"You know, for two days we tried to scare you all off. Y'all just kept comin' and comin'. You just wouldn't stop."

"Just call them plain stupid, Mr. Rudy."

"They're dumb, not stupid. Dumb! You jeopardised our whole operation, you dumb idiots."

#whiskey mountain#william grefé#1977#american cinema#nicholas e. spanos#christopher george#preston pierce#roberta collins#linda borgeson#john davis chandler#robert leslie#jerry rhodes#william kerwin#brad bond#j.g. patterson jr.#elijah perry#edward ramey#frank rickman#charlie daniels#ending my deep dive into bill Grefé's filmography for the foreseeable future whilst i nurse the brain ruptures his work has given me#expected this film (one that actually saw a decent cinema release and had recognisable if b list stars) to be one of his more accessible#and also to have been better preserved that some of the others; it isn't and it looks like shit. somehow Bill seemed to be losing his#filmmaking ability as his career progressed: sure Sting of Death was BAD but it was also campy and fun and original#this is just a sullen treasure hunt movie meets backwoods slasher with way way too much time taken up on filming dirt bike racing#not even the usually dependable Christopher George can save this from being fairly tedious and unpleasant but special mention to#Grefé mainstay JD Chandler who's the only actor who seems to actually be having fun here and delivers one of his most interesting#performances for the Florida Man of bad cinema. oh and the Charlie Daniels theme song is naturally a banger

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

#nicholas nickleby#nicholas nickleby 2002#charlie hunnam#anne hathaway#jamie bell#romola garai#nathan lane#timothy spall#kevin mckidd#alan cumming#william ash#stella gonet#tom courtenay#andrew havill#david bradley#juliet stevenson#christopher plummer#jim broadbent#edward fox#douglas mcgrath#charles dickens

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Congrats to the ultimate winner of the Hot & Vintage Movie Men Tournament, Mr. Toshiro Mifune! May he live happily and well where the sun always shines, enjoying the glories of a battle hard fought.

A loving farewell to all of our previous contestants, who are now banished to the shadow realm and all its dark joys and whispered horrors—I hear there's a picnic on the village green today. If you want to remember the fallen heroes, you can find them all beneath the cut.

What happens next? I'll be taking a break of two weeks to rest from this and prep for the Hot & Vintage Ladies Tournament. I'll still be around but only minimally, posting a few last odes to the hot men before transitioning into a little early ladies content, just like I did with this last tournament. The submission form for the Hot & Vintage Ladies tournament will remain up for one more week (closing February 21st), so get your submissions in for that asap! Once the form closes, there will be one more week of break. The first round of the Hot & Vintage Ladies Tournament will be posted on February 29th, as Leap Year Day seems like a fitting allusion to leaping into these ladies' arms.

Thanks for being here! Enjoy the two weeks off, and send me some great propaganda.

In order of the last round they survived—

ROUND ONE HOTTIES:

Richard Burton

Tony Curtis

Red Skelton

Keir Dullea

Jack Lemmon

Kirk Douglas

Marcello Mastroianni

Jean-Pierre Cassel

Robert Wagner

James Garner

James Coburn

Rex Harrison

George Chakiris

Dean Martin

Sean Connery

Tab Hunter

Howard Keel

James Mason

Steve McQueen

George Peppard

Elvis Presley

Rudolph Valentino

Joseph Schildkraut

Ray Milland

Claude Rains

John Wayne

William Holden

Douglas Fairbanks Sr.

Harold Lloyd

Charlie Chaplin

John Gilbert

Ramon Novarro

Slim Thompson

John Barrymore

Edward G. Robinson

William Powell

Leslie Howard

Peter Lawford

Mel Ferrer

Joseph Cotten

Keye Luke

Ivan Mosjoukine

Spencer Tracy

Felix Bressart

Ronald Reagan (here to be dunked on)

Peter Lorre

Bob Hope

Paul Muni

Cornel Wilde

John Garfield

Cantinflas

Henry Fonda

Robert Mitchum

Van Johnson

José Ferrer

Robert Preston

Jack Benny

Fredric March

Gene Autry

Alec Guinness

Fayard Nicholas

Ray Bolger

Orson Welles

Mickey Rooney

Glenn Ford

James Cagney

ROUND TWO SWOONERS:

Dick Van Dyke

James Edwards

Sammy Davis Jr.

Alain Delon

Peter O'Toole

Robert Redford

Charlton Heston

Cesar Romero

Noble Johnson

Lex Barker

David Niven

Robert Earl Jones

Turhan Bey

Bela Lugosi

Donald O'Connor

Carman Newsome

Oscar Micheaux

Benson Fong

Clint Eastwood

Sabu Dastagir

Rex Ingram

Burt Lancaster

Paul Newman

Montgomery Clift

Fred Astaire

Boris Karloff

Gilbert Roland

Peter Cushing

Frank Sinatra

Harold Nicholas

Guy Madison

Danny Kaye

John Carradine

Ricardo Montalbán

Bing Crosby

ROUND THREE SMOKESHOWS:

Marlon Brando

Anthony Perkins

Michael Redgrave

Gary Cooper

Conrad Veidt

Ronald Colman

Rock Hudson

Basil Rathbone

Laurence Olivier

Christopher Plummer

Johnny Weismuller

Clark Gable

Fernando Lamas

Errol Flynn

Tyrone Power

Humphrey Bogart

ROUND 4 STUNGUNS:

James Dean

Cary Grant

Gregory Peck

Sessue Hayakawa

Harry Belafonte

James Stewart

Gene Kelly

Peter Falk

QUARTERFINALIST VOLCANIC TOWERS OF LUST:

Jeremy Brett

Vincent Price

James Shigeta

Buster Keaton

SEMIFINALIST SUPERMEN:

Omar Sharif

Paul Robeson

FINALIST FANTASIES:

Sidney Poitier

Toshiro Mifune

and ok, sure, here's the shadow-bracket-style winner's portrait of Toshiro Mifune.

#hotvintagepoll#hot men finals#a winner crowned!#fuck that old man (requiem)#shadow bracket#toshiro mifune

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

Books On Books Collection - William Nicholson

View On WordPress

#C.B. Falls#Carton Moore Park#Christopher Wormell#Colin Campbell#Edward Craig#Edward Gordon Craig#Ellen Terry#Enid Marx#Henry Irving#James Pryde#Joseph Crawhall#Marguerite Steen#Nick Wonham#William Nicholson

0 notes

Text

IN THE BEGINNING, THERE WAS ONLY THE OCEAN

“Accepting the Universe” (1920), by John Burroughs; // “Literary Paper” (1855), by Edward Forbes; // “A Thousand Flamingos” by Sanober Khan; // Sylvia Earle; // “Wither” (The Chemical Garden Trilogy), by Lauren DeStefano; // “The Immense Journey” ch. The Flow of the River (1957), by Loren Eiseley; // Jacques-Yves Cousteau; // Heinrich Zimmer; // “Pictures from Brueghel and Other Poems” (1962), by William Carlos Williams; // “Sandry’s Book” (Circle of Magic Quartet), by Tamora Pierce; // “The Sea”, by Barry Cornwall (Bryan Waller Procter); // Speech at the America’s Cup Dinner (1962), by John F. Kennedy; // Jacques-Yves Cousteau; // Erica Billups; // Robert Wyland; // “Eragon” (The Inheritance Cycle Tetralogy), by Christopher Paolini; // Christy Ann Martine; // Robert Wyland; // “Le testament d'Orphée” (1960), by Jean Cocteau; // Speech at the America’s Cup Dinner (1962), by John F. Kennedy; // “The Infinite Moment of Us”, by Lauren Myracle; // “American Fantastic Tales: Terror and the Uncanny from Poe to the Pulps”, by Julian Hawthorne

#webweaving#web weaving#webweave#web weave#ocean#sea#oceancore#water#ocean aesthetic#aesthetic#poem#poetry#spilled poetry#spilled thoughts#spilled ink#quote#quotes

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

I’ve teased it. You’ve waited. I’ve procrastinated. You’ve probably forgotten all about it.

But now, finally, I’m here with my solarpunk resources masterpost!

YouTube Channels:

Andrewism

The Solarpunk Scene

Solarpunk Life

Solarpunk Station

Our Changing Climate

Podcasts:

The Joy Report

How To Save A Planet

Demand Utopia

Solarpunk Presents

Outrage and Optimisim

From What If To What Next

Solarpunk Now

Idealistically

The Extinction Rebellion Podcast

The Landworkers' Radio

Wilder

What Could Possibly Go Right?

Frontiers of Commoning

The War on Cars

The Rewild Podcast

Solacene

Imagining Tomorrow

Books (Fiction):

Ursula K. Le Guin: The Left Hand of Darkness The Dispossessed The Word for World is Forest

Becky Chambers: A Psalm for the Wild-Built A Prayer for the Crown-Shy

Phoebe Wagner: When We Hold Each Other Up

Phoebe Wagner, Bronte Christopher Wieland: Sunvault: Stories of Solarpunk and Eco-Speculation

Brenda J. Pierson: Wings of Renewal: A Solarpunk Dragon Anthology

Gerson Lodi-Ribeiro: Solarpunk: Ecological and Fantastical Stories in a Sustainable World

Justine Norton-Kertson: Bioluminescent: A Lunarpunk Anthology

Sim Kern: The Free People’s Village

Ruthanna Emrys: A Half-Built Garden

Sarina Ulibarri: Glass & Gardens

Books (Non-fiction):

Murray Bookchin: The Ecology of Freedom

George Monbiot: Feral

Miles Olson: Unlearn, Rewild

Mark Shepard: Restoration Agriculture

Kristin Ohlson: The Soil Will Save Us

Rowan Hooper: How To Spend A Trillion Dollars

Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing: The Mushroom At The End of The World

Kimberly Nicholas: Under The Sky We Make

Robin Wall Kimmerer: Braiding Sweetgrass

David Miller: Solved

Ayana Johnson, Katharine Wilkinson: All We Can Save

Jonathan Safran Foer: We Are The Weather

Colin Tudge: Six Steps Back To The Land

Edward Wilson: Half-Earth

Natalie Fee: How To Save The World For Free

Kaden Hogan: Humans of Climate Change

Rebecca Huntley: How To Talk About Climate Change In A Way That Makes A Difference

Christiana Figueres, Tom Rivett-Carnac: The Future We Choose

Jonathon Porritt: Hope In Hell

Paul Hawken: Regeneration

Mark Maslin: How To Save Our Planet

Katherine Hayhoe: Saving Us

Jimmy Dunson: Building Power While The Lights Are Out

Paul Raekstad, Sofa Saio Gradin: Prefigurative Politics

Andreas Malm: How To Blow Up A Pipeline

Phoebe Wagner, Bronte Christopher Wieland: Almanac For The Anthropocene

Chris Turner: How To Be A Climate Optimist

William MacAskill: What We Owe To The Future

Mikaela Loach: It's Not That Radical

Miles Richardson: Reconnection

David Harvey: Spaces of Hope Rebel Cities

Eric Holthaus: The Future Earth

Zahra Biabani: Climate Optimism

David Ehrenfeld: Becoming Good Ancestors

Stephen Gliessman: Agroecology

Chris Carlsson: Nowtopia

Jon Alexander: Citizens

Leah Thomas: The Intersectional Environmentalist

Greta Thunberg: The Climate Book

Jen Bendell, Rupert Read: Deep Adaptation

Seth Godin: The Carbon Almanac

Jane Goodall: The Book of Hope

Vandana Shiva: Agroecology and Regenerative Agriculture

Amitav Ghosh: The Great Derangement

Minouche Shafik: What We Owe To Each Other

Dieter Helm: Net Zero

Chris Goodall: What We Need To Do Now

Aldo Leopold: A Sand County Almanac

Jeffrey Jerome Cohen, Stephanie Foote: The Cambridge Companion To The Environmental Humanities

Bella Lack: The Children of The Anthropocene

Hannah Ritchie: Not The End of The World

Chris Turner: How To Be A Climate Optimist

Kim Stanley Robinson: Ministry For The Future

Fiona Mathews, Tim Kendall: Black Ops & Beaver Bombing

Jeff Goodell: The Water Will Come

Lynne Jones: Sorry For The Inconvenience But This Is An Emergency

Helen Crist: Abundant Earth

Sam Bentley: Good News, Planet Earth!

Timothy Beal: When Time Is Short

Andrew Boyd: I Want A Better Catastrophe

Kristen R. Ghodsee: Everyday Utopia

Elizabeth Cripps: What Climate Justice Means & Why We Should Care

Kylie Flanagan: Climate Resilience

Chris Johnstone, Joanna Macy: Active Hope

Mark Engler: This is an Uprising

Anne Therese Gennari: The Climate Optimist Handbook

Magazines:

Solarpunk Magazine

Positive News

Resurgence & Ecologist

Ethical Consumer

Films (Fiction):

How To Blow Up A Pipeline

The End We Start From

Woman At War

Black Panther

Star Trek

Tomorrowland

Films (Documentary):

2040: How We Can Save The Planet

The People vs Big Oil

Wild Isles

The Boy Who Harnessed The Wind

Generation Green New Deal

Planet Earth III

Video Games:

Terra Nil

Animal Crossing

Gilded Shadows

Anno 2070

Stardew Valley

RPGs:

Solarpunk Futures

Perfect Storm

Advocacy Groups:

A22 Network

Extinction Rebellion

Greenpeace

Friends of The Earth

Green New Deal Rising

Apps:

Ethy

Sojo

BackMarket

Depop

Vinted

Olio

Buy Nothing

Too Good To Go

Websites:

European Co-housing

UK Co-housing

US Co-housing

Brought By Bike (connects you with zero-carbon delivery goods)

ClimateBase (find a sustainable career)

Environmentjob (ditto)

Businesses (🤢):

Ethical Superstore

Hodmedods

Fairtransport/Sail Cargo Alliance

Let me know if you think there’s anything I’ve missed!

#solarpunk#hopepunk#cottagepunk#environmentalism#social justice#community#optimism#bright future#climate justice#tidalpunk#turbinepunk#resources#masterpost#books#films#magazines#podcasts#apps

1K notes

·

View notes